JUNE 2014

Click title to jump to review

THE COUNTRY HOUSE by Donald Margulies | Geffen Playhouse

THE CURSE OF OEDIPUS adapted by Ken Cavander | Antaeus Company

THE DEATH OF THE AUTHOR by Steven Drukman | Geffen Playhouse

GRUESOME PLAYGROUND INJURIES by Rajiv Joseph | Rogue Machine Theatre

STONEFACE by Vanessa Claire Stewart | Pasadena Playhouse

STUPID FUCKING BIRD Chekhov adapted by Aaron Posner | The Theatre @ Boston Court

Craftsman home

There is an inviting, lived-in quality to John Lee Beatty’s country house set for the world premiere of Donald Margulies' latest play. Similarly, the Pulitzer Prize-winning author of Dinner with Friends has furnished The Country House, directed by Daniel Sullivan at the Geffen Playhouse (through July 13), with recognizable themes and characters.

We are familiar with Margulies' art of placing creative people at the center of his plays: painter Jonathan Waxman in Sight Unseen, short story writer Ruth Steiner in Collected Stories, novelist Eric Weiss in Brooklyn Boy, and photojournalist Sarah Goodwin in Time Stands Still. With The Country House, at long last, he comes home to the theater.

Not only are the seven characters – including one whose death a year earlier reunites them – of the theater, the dialogue is enlivened with plenty of industry references and assessments of this lively art's health and influence. Resonating in the background, tying tone and circumstances together like painter's wash, is the work of Anton Chekhov. We catch glimpses of The Seagull's Irina Arkadina in Anna Patterson, a Broadway star with a history of headlining productions at nearby Williamstown Theatre Festival, and of Uncle Vanya's title character in her desperate son Elliott.

It is not Margulies' style to sacrifice creativity to homage-paying: He has not dropped his Country House into The Cherry Orchard. However, these theatrical roots make their way far enough onto the boards to add what for Chekhov was ennui and stasis, but here feels like a placidity and lack of dramatic substance.

Nevertheless, Margulies is a master craftsman whose dialogue drives the play. His exposition appears to drop randomly as if blown in on a breeze. Anna (Blythe Danner) is matriarch of three generations with theater in the blood. But, reflecting theater's weakening grasp on popular culture, that bloodline has thinned. She remains the embodiment of theatrical tradition, back to star in Williamstown's summer production of Mrs. Warren's Profession.

The beginning of rehearsals coincides with the anniversary of her daughter Cathy's cancer death. Joining her to mark the occasion are the widower, Walter Keegan (David Rasche), a former theater director now rich from lucrative action-adventure film franchises, and their daughter Susie, finishing studies in Religion and Psychology at Yale. Elliott (Eric Lange), an actor more mired in theater than embracing it, was overshadowed by his more talented sister and wears his mourning heavily about him. We discovered his bitterness owes more to the loss of any career prospects.

Two more actors round out the group. Walter is introducing his girlfriend Nell McNally (Emily Swallow) while Michael Astor, an old family friend and one of Cathy's early lovers, has the living room couch while his Williamstown housing is prepared. Michael's hit series and handsomeness have given him the kind of fame that earns "Sexiest Man Alive" headlines on People Magazine. He is in town for a production of The Guardsman.

No threats with the gravity of Cathy's prolonged illness threaten the calm of The Country House. Instead, we have Susie's adolescent irritation with her father's need to move on, Michael's ungracious midnight move on Nell, and Anna's too-gracious hit on her couch 'tomato.'

Only Elliot has any substantial arc, and after his displays of meanness and delusion, we have ceased to care about him. To be talent-free and yet hope to impress his mother with his first playwriting attempt is understandable. To drink too much and get nasty is nothing new. Even misfiling Nell's kindness during a Humana Festival 11 years before under romance is excusable. However, all – and more – combined, while the other characters are so likeable, is unrealistic and distances us. It would help us invest emotionally in Elliott if, for instance, Nell mistakenly got intimate one night in the room they shared in Louisville. She could immediately have regretted it, but at least Elliott gets something on which to hang his blazing torch.

Sullivan, who has been Margulies' director of choice since Dinner with Friends, again works his magic. He has cast well and steers the portrayals of every character, except Elliott, to be likeable. Anna, for instance, could be more imperious and less willing to abort her seduction attempt. Though Rasche is so wonderfully appealing, Walter could use some disingenuousness to liven things up. It's there in his absence of closeness with Susie, he just needs to sacrifice some of his charisma.

While the characters' discussion of theater's relative merits doesn't add new insights, it's refreshing that Margulies gives theater no preferential treatment. Why art is important and distinct, if not mutually exclusive, from entertainment isn't made clear in the discussion. Perhaps the debate is settled in choices like these, in which the conflict that creates art is stifled for the crowd-pleasing comedy that has made this a hit – and surely will continue when the show opens at the commissioning Manhattan Theatre Club this fall.

top of page

THE COUNTRY HOUSE

by DONALD MARGULIES

directed by DANIEL SULLIVAN

GEFFEN PLAYHOUSE

June 3-July 13, 2014

(Opened 6/11, Rev’d 6/15e)

CAST Blythe Danner, Scott Foley, Eric Lange, David Rasche, Sarah Steele, Emily Swallow u/s Michael Canavan, Marnie Mosiman, Jill Renner, Daniel Travis

PRODUCTION John Lee Beatty, set; Rita Ryack, costumes; Peter Kaczorowski, lights; Jon Gottlieb, sound; Peter Golub, music; Young Ji/Maggie Swing, stage management

HISTORY Commissioned by Manhattan Theatre Club, with funding support from Bank of America; World Premiere

Blythe Danner, Scott Foley and Eric Lange | Michael Lamont

Going to the gods

For Ken Cavander's unification of Socrates' three plays about Oedipus and his family into a single odyssey called The Curse of Oedipus, he calls not on the priest of Zeus who appears in the original, but on Zeus' two sons. This sends the story's generational theme echoing off Olympus and gives Cavander and director Casey Stangl a way to add comic relief to The Antaeus Company's world premiere (through August 10).

Zeus' sons, Dionysius (Stoney Westmoreland) and Apollo (Barry Creyton), observe from a platform above François-Pierre Couture's set of concentric pavers and floor-to-ceiling bungee cords that may be marionette controls, celestial strings, or simply fate's invisible webbing. Creyton and Westmoreland provide lively counterpoint to the tragedy of Oedipus, his parents, and children. Their play-by-play slides into step-sibling squabbling, as purebred Apollo and half-mortal Dionysius take sides in assessing the human condition.

Credit Cavander with unbinding the three plays' pages to be organized lineally from Oedipus' birth through his transcendence. If Cavandar commits any sing, it is not one of hubris but over-devotion. While The Curse of Oedipus is engaging for the bulk of its two acts and two-hour, 40 minutes, thanks in great part to Stangl's ability to inject movement and energy, its achievement lies more in being comprehensive than captivating.

Oedipus (Terrell Tilford), whose name roughly translates to "swollen foot," was named by his adoptive parents, King Polybus and Queen Merope of Corinth. They had received the baby from a man who found him on a mountainside where King Laius of nearby Thebes had set him to die. Laius and his wife, Jocasta, did this to thwart a prophecy that their son would one day kill him and marry her. Unknown to them, he survived and grew strong, eventually learning his curse and, assuming Polybus and Merope were the parents he would target, he moves to Thebes to get them out of harm's way. On the road he confronts an obstinate traveler who challenges him. In the fight, the man and all but one of his servants is killed.

The surviving Manservant (Chad Borden) returns to inform Creon (Tony Amendola), Jocasta's brother, of the murder, lying that there were many assailants. Oedipus, arriving alone, is not suspected of being Laius' killer. He also solves the riddle of the sphinx, ending a horrible curse on the people and their harvests. Exalted, he marries Laius' widow and assumes the throne, begetting Antigone (Kwana Martinez), Eteocles (Douglas Dickerman), Ismene (Lindsay LaVanchy), and Polyneices (J.B. Waterman).

With Dionysius and Apollo providing their bemused commentary, Oedipus discovers that his and Laius' efforts to foil fate only succeeded in their fooling themselves. The original plays were not written as a cycle and there are discrepancies in the events. When he has the option, Cavander generally chooses to let a character live. Such is the case with Jocasta, who often kills herself after learning of her innocent incest. Here she does not, but, true to form, Oedipus gouges out his eyes. The story continues as a multi-generational game of jockeying for power. With Oedipus self-deposed, the brothers' contested claims are solved by Creon's idea that they annually alternate shared reign. That doesn't last long and war breaks out, leaving Polyneices dead, seguing into Antigone's famous showdown with Creon and Eteocles in which she insists her brother be buried.

Cavander allows the complex tale to proceed smoothly and dramatically. All the connections are laid out with historic clarity, with our two narrators helping to keep the broad perspective of man and god. The ensemble that fills in as chorus and several smaller parts is a diverse group including Ned Schmidtke, John Achorn, Rafael Goldstein, Chris Clowers, Reba Waters Thomas, Susan Boyd Joyce, Desireé Mee Jung and Keri Safran. Percussive accent and underscoring are provided by drummer Geno Monteiro, who remains onstage throughout.

As Oedipus, Tilford gives the cursed king a powerful physical presence that dominates his scenes. Ms. Gordon is another standout as Jocasta, eternally cursed for allowing self-preservation to determine her child's fate.

It is Creon that clearly emerges as the most important second character. Because he is stitched from timelines created in different sources, he acts on apparently conflicting motivations. As a result, his inner development is more problematic and his role, as important to Oedipus the as Iago is to Othello needs more clarity. For his part, Amendola shifts from concerned family man to conniving in-law with his usual adroitness, but the arc could be more focused.

This is another Herculean effort by Antaeus that pays rewards both artists and audiences. It's a mammoth undertaking and a huge budgetary challenge, especially with the theater's double-casting policy that fills each role with two strong actors in rotation. The alternate performers are listed at right in parentheses.

top of page

THE CURSE OF OEDIPUS

by KEN CAVANDER

directed by CASEY STANGL

ANTAEUS THEATER COMPANY

May 20-June 29, 2014

(Opened 5/28, Rev’d 6/22m)

CAST* John Achorn (Drew Doyle), Bernard K. Addison (Fran Bennett), Tony Amendola (Josh Clark), Chad Borden (Bill Mendieta), Chris Clowers (Harry Fowler), Barry Creyton *(Mark Bramhall), Douglas Dickerman Patrick Wenk-Wolff), Rafael Goldstein (Cameron J. Oro), Eve Gordon (Rhonda Aldrich), Susan Boyd Joyce (Kitty Swink), Desireé Mee Jung (Belen Greene), Jonathon Lamer (Lee Jones), Lindsay LaVanchy (Lily Nicksay), Kwana Martinez (Joanna Strapp), Geno Monteiro (Adam Meyer - drummers), Keri Safran (Sylvie Mae Baldwin, Anna Quirino-Miranda), Ned Schmidtke (Philip Proctor), Adam J. Smith (Dylan John Seaton), Reba Waters Thomas (Elizabeth Swain), Terrell Tilford (Ramon de Ocampo), J.B. Waterman (Brian Tichnell), Stoney Westmoreland (John Apicella) (*names in parentheses are alternating actors)

PRODUCTION François-Pierre Couture, set/lights; E.B. Brooks, costumes; Jeff Gardner, sound; Adam Meyer, props; Lara E. Nall/Kristin Weber, stage management

HISTORY Originally produced at the Williamstown Theatre Festival in a two-evening version, entitled The Legend of Oedipus, directed by Nikos Psacharopoulos. Developed by the Antaeus Company under direction of Casey Stangl. World Premiere

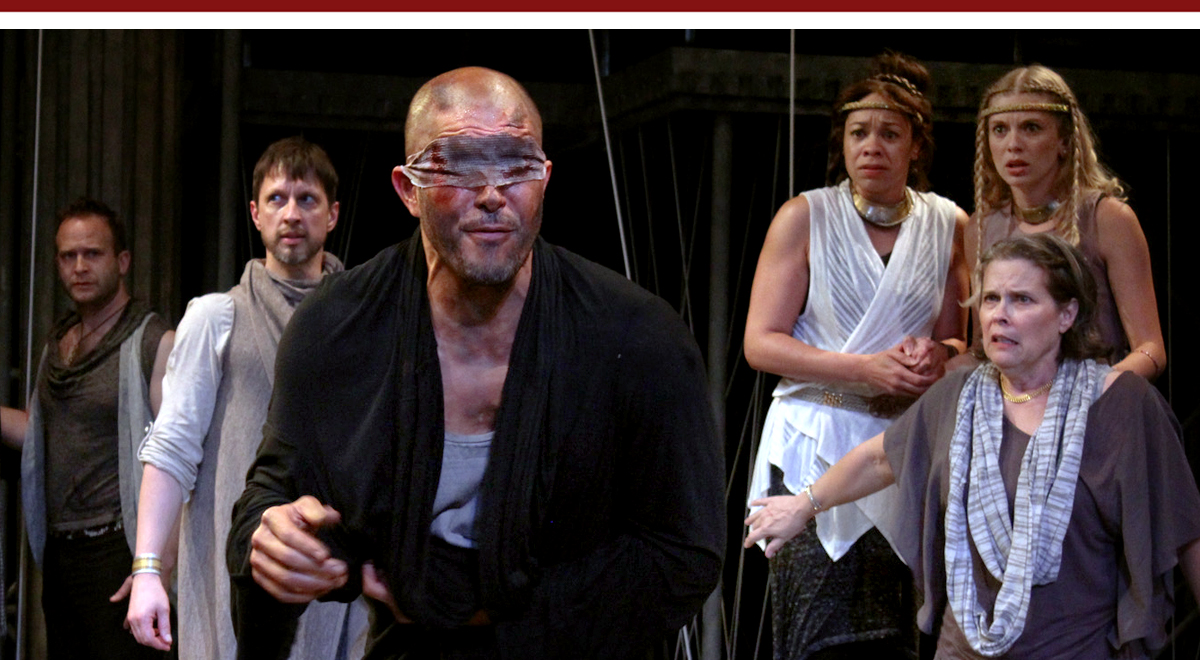

Adam J. Smith, Chad Borden, Terrell Tilford, Kwana Martinez, Lindsay LaVanchy and Susan Boyd Joyce | Maia Rosenfeld

Unnatural selection

Back in 1967, when Roland Barthes authored The Death of the Author, he wrote that "the birth of the reader must be at the cost of the death of the Author." Now, a generation after the birth of Adobe Reader, when Internet Googling has replaced library Xeroxing for gathering source material, students have gotten smarter as their professors have become more suspicious.

Steven Drukman cites a source right up front in his new play, Death of the Author, receiving its Geffen Playhouse premiere (through June 29) under Bart DeLorenzo's respectful direction. The drama pushes academic and cultural hot buttons as a relatively inexperienced adjunct professor is first suspicious and then suspect in an end-of-term showdown with his student. Only after the student's allegations lead to a citation for impropriety that the professor sees how his own prejudice may have influenced him.

Drukman uses Barthes pioneering work in literary criticism as subject matter for the university class taught by Jeff (David Clayton Rogers). It is a week before graduation and Jeff is meeting with Bradley (Austin Butler) to discuss the final paper that will count for his grade. He points out many recognizable but unattributed excerpts from published work. He doesn't say the "P-word," hoping that Bradley will confess on his own and agree to quickly hand in a second paper of all original ideas.

Instead of caving in, Bradley insists the stitched-together paper fulfills the assignment in its form, which manifests Barthes' deconstructionism theories in reducing the presence of the author. The impasse means the discussion moves up the chain of command to department chair J. Trumbell Sykes (Orson Bean). Because Sykes, a giant in his field with numerous acclaimed texts of his own, is the academic hero of his estranged girlfriend, Sarah (Lyndon Smith), Bradley is excited by the chance to meet him. A pre-law and math student who only took the literature class to get back with Sarah, has a great excuse to talk to her again.

When Sykes more or less sides with the student, the discussion needs to be resolved by the dean. But Bradley slips in ahead of schedule, and unwittingly drops off a list of bullet-points he and Sarah compiled. It includes innuendoes that Jeff's personal interest in Bradley owes more to his being gay. The notes become accusations that derail Jeff's fast track for advancement.

In a somewhat forced turn of events to that resolve Death with a happy ending, Jeff realizes something about himself. The copying he really resents is generational, in which wealthy families like Bradley's pull strings to ensure their children maintain their advantage and privilege. In this we hear echoes of Wendy Wasserstein's Third, seen at the Geffen in 2007. [review]

It's an entertaining 90-minute one-act with the patina of academic verisimilitude. Drukman is a fine dramatist, whose In This Corner was a favorite in 2008. [review] DeLorenzo continues his ability to generate great work from his solid cast without leaving fingerprints on the action. He gets special thanks for giving such a fine showcase to Bean, who made his Broadway debut more than 60 years before this production began.

Takeshi Kata has designed a mirror-lined cube that suggests both academia's need to reflect on the world and its own navel-gazing insularity. The old desks and chairs that glide in on palettes, as well as Christina Haatainen Jones' natural, earth-tone costumes are offset against the high-gloss walls, as if liberal arts departments like this one are hold-outs against the surface gleam of our technology-driven age. Kudos to Lap Chi Chu for lighting this tricky environment and to John Ballinger for the sound and music that enlivens it.

top of page

DEATH OF

THE AUTHOR

by STEVEN DRUKMAN

directed by BART DeLORENZO

GEFFEN PLAYHOUSE

May 20-June 29, 2014

(Opened 5/28, Rev’d 6/22e)

CAST David Clayton Rogers, Austin Butler, Orson Bean, Lyndon Smith

PRODUCTION Takeshi Kata, set; Christina Haatainen ones, costumes; Lap Chi Chu, lights; John Ballinger, music/sound; Cate Cundiff/Jessica Aguilar, stage management

HISTORY Recipient of the Edgerton Foundation New American Play Award and a Theater Development grant from the Laurents/Hatcher Foundation World Premiere

David Clayton Rogers, Austin Butler, Orson Bean | Michael Lamont

The first cut . . .

In the two years between writing his big canvas fantasia, Bengal Tiger at the Baghdad Zoo, and its Pulitzer nomination and Broadway run, Rajiv Joseph took a two-character look at childhood wounding. In Rogue Machine Theatre's L.A. premiere of Gruesome Playground Injuries, directed by Larissa Kokernot at Theatre/Theater (extended through August 4), we see Joseph getting big resonance from the small canvas.

At 40, the prolific Cleveland-born playwright is only a decade into a career that began after three years with the Peace Corps in Senegal and an MFA in dramatic writing from NYU. His first play, Huck and Holden, was his introduction to L.A. a year after its 2005 premiere at the Alley Theatre. After several more successes, Bengal Tiger premiered here at the Kirk Douglas Theatre in May 2009, and on Broadway in March 2011.

Joseph rewards attentive audiences by letting the thread of his story appear to unreel itself, as if coaxed out by a drifting floater. Kokernot's staging enhances the pace of revelation as the actors reset furniture, then introduce each of the eight scenes as substitute teachers introduce themselves. On a chalkboard they print the next scene's title and character age. Injuries covers a quarter century in five-year intervals, but other than the opening scene, when they are 8-year-olds, and the final one at age 33, the story follows revelations rather than chronology.

David Mauer's set begins as a grade school Nurse's Office. Doug has just been treated after the first of a series of accidents that, while usually his own stupid fault, result in physical injuries of Biblical proportions. Eyes are gouged out. Lightening strikes him. He loses the use of his legs. However, this first wound to his forehead is the only "playground" injury and so we turn our attention to the other 8-year-old we met in the Nurse's Office.

We will discover that, while careful not to accidentally hurt herself, Kayleen has persistent stomach pains and later that she self-inflicts wounds through "cutting." With a survivor's reluctance to dignify her abuse by revisiting it, Kayleen will not speak to her original childhood wounds, which are emotional injuries. Like an untreated wound seeping through clothing, they will become obvious. A portrait gradually emerges of parents who were neglectful at best and abusive at worst. As if to abet her denial, Joseph's title deflects our attention back to Doug's calamities.

Though Kayleen rarely allows herself to be approachable, and the two friends spend little time together, Doug falls in love with her. In the way she remains beautiful while her psyche continues to scar, his inner world is the opposite of his physical misfortunes. His emotionally healthy childhood has left him happy and communicative. But his growing adoration is relegated to a friendship that she refuses to nourish but tellingly depends on. In an echo of Job, who would not abandon God despite unconscionable suffering, Doug remains faithful.

Joseph and Kokernot do not permit artificially happy endings. They do, however, allow Kayleen to crack open the door she has bolted between them, just enough to let in a final ray of hope as the lights fade.

This reviewed performance was simultaneously operating in another theatrical dimension. The handful of bouquets that had sprouted in our matinee gallery identified nurturing family and friends of Tania Verafield and Ryan Mulkay, the two alternates for regulars Jules Willcox and Brad Fleischer who were getting their first scheduled appearance. Fleischer, who created the role back in Texas in 2009, and Willcox were so good in their parts that the play has had a critically acclaimed extension of more than a month. Though Verafield and Mulkay are seasoned pros, a relay hand-off during a successful run is an anxious moment for actors.

Solidly off book, Verafield and Mulkay quickly had the play's tone and got the pivotal first scene right. They do not play 8-year-olds as immature, but as people without the experience to deal with the complex, scary situations into which they're thrown. We see them adapt what is happening to fit their developing awareness. The actors also deftly executed all the choreographed scene changes without hesitation.

Verafield has a tricky assignment. She must bury all the motivations that help the audience understand her character, and attract Doug while making it clear she doesn't want to be involved with him, but instead prefers random episodes with neglectful lovers. She made sense of it all and certainly more performances could only give her more insight and nuance. For his part, Mulkay successfully grounds a character who could easily seem ridiculous. Despite his loss of sight and being confined to a wheelchair, his overriding need to love and mend his lifelong friend needs to make perfect sense and he achieved that beautifully.

On this Saturday afternoon, we believe Kayleen and Doug deserved their ray of hope, and know that Verafield and Mulkay earned their bouquets.

top of page

GRUESOME PLAYGROUND INJURIES

by RAJIV JOSEPH

directed by LARISSA KOKERNOT

ROGUE MACHINE THEATRE

May 24, 2014

(Opened 4/24, Rev’d 3/15m)

CAST Brad Fleischer, Jules Willcox; u/s Tania Verafield, Ryan Mulkay

PRODUCTION David Mauer, set; Halei Parker, costumes; Dan Weingarten, lights; Colin Wambsgans, sound; Jennifer McHugh, props; Ramón Valdez, stage management

HISTORY Originally produced by the Alley Theatre; Los Angeles Premiere; Produced by John Perrin Flynn & David Mauer

Jules Willcox and Brad Fleischer | John Flynn

Tough transitions

French Stewart is a great asset for Los Angeles theater. For years his detailed characterizations have amplified the humor in many comedies. He made Gregg Henry's fine Little Egypt funnier and Justin Tanner's not-so-fine Voice Lessons believable. He also made the Buster Keaton bio-play Stoneface a critically acclaimed hit for Sacred Fools in 2012.

Stewart's brand of thoughtful, controlled work is right for Keaton, who along with Charlie Chaplin, Harold Lloyd and Stan Laurel was one of the creative geniuses of early film comedy. Raised on the stage, in his parents' especially brutal Vaudeville act, he was getting tossed about the boards when most kids are in kindergarten. Maintaining a disaffected stoicism despite the childhood busting up he endured became a trademark and earned him a new first name as well as the nickname "The Great Stoneface." After maturing into a solo act, he moved into film and rose to the top on an endless series of stunts combining boundless imagination and physical risk.

But trouble making the transition to talkies, fights with studio heads, feuds with ill-chosen spouses, and bouts of alcoholism would derail his career. He fell into a creative dry spell while drying out in sanatoria like Arrowhead Springs, near San Bernardino, where his story begins in Stoneface.

With its Hollywood storyline about decline and resurgence, and Stewart still an industry insider from his years on TV's hit "3rd Rock from the Sun," Stoneface seems a perfect choice for Pasadena Playhouse's own rebound from bankruptcy a few years ago. But in its transition to the "big screen," too much production has undermined what must have been a very intimate experience back at Sacred Fools. The fact that performances were added to the run is good news, but that the extension ad went back to the 2012 L.A. Times and L.A. Weekly reviews for the most exciting quotes suggests there indeed was, by comparison, a fall-off in impact for 2014.

Playwright Vanessa Claire Stewart has made a chopped salad of the Keaton timeline, and despite having each new time and setting projected above the stage it's easy to get confused as to where we are in Keaton's story. It's especially problematic when the narrative seeks to tell, as the subtitle says, "The Rise and Fall and Rise of Buster Keaton." Director Jaime Robledo has surrounded Mr. Stewart with a solid cast, but the exaggerated acting style used to recall the silent film recreations occasionally seeps into the "off-screen" performances. It's another symptom of the bigness diminishing the heart.

The physical production does have its moments, and the best one comes right at the beginning when the transition from film to theater is made manifest in a little sleight-of-hand. It's not only the best moment in the show, it could be the best technical device of the theater season, as live performers slip into a two-dimensional film projection. It won an Ovation Award for 2012, and sets a high bar for the rest of the show, doing for Stoneface what Jeff Daniel's movie-escape did for Woody Allen's Purple Rose of Cairo. Unfortunately, the rest of the stylistic interplay between silent film, talkies, and theater are nowhere near as successful.

Ms. Stewart also adds the device of dividing the conflicted Keaton into two parts – man and artist. Joe Fria is likeable as the younger, sober Buster, but, it's hard to imagine Mr. Stewart couldn't have given us the whole man in a script that was better at taking us through the artist-man's tortured journey.

The cast also includes Scott Leggett as the even more tragic figure of Roscoe "Fatty" Arbuckle, and the wonderful Daisy Eagan as a star-struck sanatorium nurse. Tegan Ashton Cohan and Rena Strober are delightful as two of the famous Talmadge sisters, while Pat Towne can't do much with the cardboard character of mogul Louis B. Mayer, and likewise for Jake Broder's Joseph Schenck, another famous early Hollywood producer. Guy Picot, however, is a bright spot as the sympathetic Chaplin.

Though Robledo's direction and the entire production suffer a "more is less" syndrome, the design team have done what was asked of them and must be commended for the execution. Joel Daavid designed the set, Jessica Olson the costumes, Jeremy Pivnick the lights, and Crickett Myers the sound. Ben Rock and Anthony Backman, who created the projections and, we assume, the inter-dimensional film, get the big kudos. Those transitions the actors make, slipping behind the projection screen just as they appear in the previously filmed exterior, must involve some of the best-timed cueing in stage management history. Hats off to Susie Walsh and Hethyr Verhoef, who run the show, and Technical Director Brad Enlow for getting it all together.

top of page

STONEFACE

by VANESSA CLAIRE STEWART

directed by JAIME ROBLEDO

PASADENA PLAYHOUSE

June 3-29, 2014

(Opened 6/8, Rev’d 6/15m)

CAST Jake Broder, Tegan Ashton Cohan, Conor Duffy, Joe Fria, Ryan Johnson, Scott Leggett, Guy Picot, French Stewart, Rena Strober, Pat Towne

PRODUCTION Joel Daavid, set; Jessica Olson, costumes; Jeremy Pivnick, lights; Cricket S. Myers, sound; Ben Rock/Anthony Backman, projections; Ryan Johnson, music; Jessica Mills, wigs; Mike Mahaffey, fights; Susie Walsh, stage management

HISTORY Originally produced by Sacred Fools Theater Company

Jake Broder, French Stewart, Tegan Ashton Cohan and Rena Strober | Jim Cox

Flipping the bird

Aaron Posner's new adaptation of The Seagull does more than revive Anton Chekhov's 1896 Russian classic about longing for love and significance. It reinvigorates theater with energy and intent that bursts through the fourth wall like a dam spilling its guts onto a parched floodplain.

The West Coast premiere of Stupid Fucking Bird is a deliriously irreverent co-production by The Theatre at Boston Court and Circle X Theatre Company (extended through August 10 at Boston Court). Director Michael Michetti's seven cast members do a Janus-dance along the actor-character seam, managing simultaneously to be performers and observers.

The physical environment also co-exists as reality and representation. We are on the estate of successful film and television actress Emma Arkadina (Amy Pietz), but Stephanie Kerley Schwartz's unpainted particleboard is a constant reminder of the stage. The famous writer Trigorin, with the new first name of Doyle (Matthew Floyd Miller), is Emma's younger lover. Her son, Conrad Arkadina (Will Bradley) is still immobilized by unrequited love for Nina Zachery (Zarah Mahler), but by changing his surname from Treplyov, Posner hints that what's really strangling Con are apron strings. Emma's older brother Sorin and the gentle Dr. Dorn have merged into Dr. Sorn (Arye Gross), while Masha is a curt Mash (Charlotte Gulezian). Masha's cook and caretaker parents are gone, so Mash inherits those tasks. Medvedenko, the local teacher who loves her, is now Dev Dylan (Adam Silver).

The actors wander on stage as if late for pre-show warm-ups and eye the audience until Bradley announces "The play will begin when someone says: 'Start the fucking play.'" Someone obliges and we're now in subversive collusion as Mash kicks things off, brushing off Dev's interest in her gloomy wardrobe with a sarcastic "black is slimming," then admitting she "is mourning" for her life.

Con has channeled his raging passions for Nina and his desperate need for his mother's approval into penning a one-woman play. "Here We Are" is a gangly attempt at revolutionizing theater that Nina, equally desperate to be a serious actress, gamely dives into. Though its cry for immediacy is admirable it suffers from its own toxins, like someone mishandling anthrax, and alienates its audience.

While Con isn't talented enough to pull off insurrection, Posner and Michetti are, and create a channel-surfing whirl of styles and periods. Michetti gives distinct shape to scenes that are subtitled in the script. In one, non-participating actors watch from the sidelines. In another the cast perches on folding chairs as in a post-show talk back. There is a mock-Russian dance and another that turns Chekhov's familiar circle of unrequited love into a crisscrossing promenade.

Bradley gives us a high-octane Con, physicalizing his frustration by contorting and twisting himself like a wire sculpture. Pietz tucks Emma's outsized irritations and passions under celebrity cool until son and lover, respectively, bring them to the surface. Miller is just as cool and confident: despite the rocky relationship, these two clearly belong together.

Gross has mastered the art of dignifying the dismissed outsider and his Sorn is at once full of yearning and resignation. At a party thrown for his 60th birthday, he at last demands to be heard, then offers his best shot at wisdom. It's ultimately just revealing comments about regrets, both letting them build and letting them go. Gulezian's Mash is a highlight as she sings with ukulele accompaniment that undermines her gloomy tunes with sweetness. That she gradually lets Silver's lovely, lovesick teacher join her gives the romantics in the audience reason for hope.

And then, in the middle of the burlesquing, Mahler and Bradley carve out a couple moments of such emotional purity that Bird briefly eclipses the best "straight" Seagull. In her final scene, Ms. Mahler is sublimely heartbreaking as the mentally adrift and directionless Nina.

Michetti and his designers do their part, adding occasional grace notes like the sound cue for startled birds flying off when Dev blurts out a confession, or the rippling light cue when Nina toes the lake surface. Costumer Mallory Kay Nelson's rack suits the show's actor-character divide, and Elizabeth Harper finds the right light, whether it's to illuminate the entire theater or the intimate kitchen unit in Act II. Rob Oriol's original music and sound design and especially Sean Cawelti's inventive projections and graphics keep us tuned in and on our toes. Posner and Michetti have succeeded in a too-rare example of theater's "here-we-are" immediacy, in a way that audiences and actors get to share in the amazement.

top of page

STUPID FUCKING BIRD

by AARON POSNER

sort of adapted from 'The Seagull' by Anton Chekhov

directed by MICHAEL MICHETTI

THE THEATRE @ BOSTON COURT

June 19-July 27, 2014 (Opened, Rev’d 6/28e, extended through August 10)

CAST Will Bradley, Arye Gross, Charlotte Gulezian, Zarah Mahler, Matthew Floyd Miller, Adam Silver, Amy Pietz; u/s John Bobek, Emily Goss, Travis Michael Holder, Jolene Kim, Jeffrey Alan Nichols, Stasha Surdyke, Mark McClain Wilson

PRODUCTION Stephanie Kerley Schwartz, set; Mallory Kay Nelson, costumes; Elizabeth Harper, lights; Rob Oriol, sound/music direction; Sean Cawelti, projections; Jenny Smith, props; Kate Jopson, dramaturg; Andrew Lia, stage management

HISTORY Co-produced by The Theatre @ Boston Court and Circle X Theatre Co.; with support from the Edgerton Foundation, Los Angeles County Board of Supervisors/ County Arts Commission, The Shubert Foundation, The Harold and Mimi Steinberg Charitable Trust; West Coast Premiere