JANUARY 2008

Click title to jump to review

AS MUCH AS YOU CAN by Paul Oakley Stovall | Celebration Theatre

BLOODY, BLOODY ANDREW JACKSON by Alex Timbers and Michael Friedman | Kirk Douglas Theatre

THE END OF THE TOUR by Joel Drake Johnson | The Road Theatre

IN THIS CORNER by Stephen Drukman | The Old Globe

ORSON'S SHADOW by Austin Pendleton | Pasadena Playhouse

POST MORTEM by A.R. Gurney | Hyperion Lyric Theatre Cafe

SEA OF TRANQUILITY by Howard Korder | The Old Globe

TRANCED by Bob Clyman | Laguna Playhouse

More than you bargain for

Last year, two local productions showed the benefits of writers directing their own work in Ed Begley Jr.’s Ruben & Cesar and Jane Anderson’s The Quality of Life, both highlights of the season. In the West Coast premiere of Paul Oakley Stovall’s As Much as You Can, now through January 27 at Celebration Theatre, we see that a writer’s vision can be equally well-served when the playwright assumes the pivotal acting role. Stovall, a talented actor keenly attuned to the rhythm and nuance of his language, takes his place in a seamless ensemble to play Jesse, a brother who will no longer apologize to his loved ones for the one he’s chosen to love.

Celebration Theatre, celebrating its 25th season of presenting theater of particular relevance to the Gay and Lesbian community, has in Stovall’s play, as much as one can imagine, a signature production. It is at once kitchen-sink direct and – for mainstream audiences at least – revolutionary. Its nuclear unit of six family and friends creates a racial and sexual rainbow with enough diversity to serve as a starter kit for the world-at-large to learn understanding and acceptance.

Stovall's microcosm has one major conflict: Jesse's strained relationship with his older sister Evy (Tony Award-winner Tonya Pinkins, except on January 17 and 18, when J. Karen Thomas steps in). Evy is well- aware that Jesse is gay, but she prays for divine "intervention" to "reorient" him.

Appropriately, the Jesse-Evy head-on is fated to occur during a family reunion required for younger brother Tony’s (Andrew Kelsey) wedding. Coming to Chicago for the nuptials means a visit to the traditional family home (maintained by Evy and her husband) and an earful of the traditional family values (mainlined by Evy). Arriving from Europe is half-sister Ronnie (Yassmin Alers), a bi-cultural, bi-racial, bi-sexual beauty. Driving in from New York with Jesse is his life-long soul mate Nina (J. Nicole Brooks), a confirmed and constantly prowling Lesbian. The willing newcomer to the menagerie is Jesse’s Swedish-born lover, Christian (Wes Ramsey), father of a 12-year-old son he hopes to have live with him and Jesse at some point. It doesn’t take long for Christian, a professional photographer, to realize that his assignment to video-tape the wedding is part of a clumsily applied beard to make him appear Jesse's "hire" rather than "husband."

Director Krissy Vanderwarker exhibits a light touch. There are no forced moves, and she does well battling a stage left post that cuts into anything more than halfway upstage. (Attendees are advised to sit house left even if it means getting closer to the proscenium.) Her cast fills their roles admirably, not only in terms of acting, but in terms of physical qualities that support the variety of racial mixing. While the two- person face-offs sizzle with authenticity the group scenes have a spontaneous feeling, like we're spending an afternoon with lively friends who have great facility for playful truth-telling. They just happen to be going through some major family dramas that are instructive for society as a whole.

Vanderwarker and her designers/production people have allowed the show a family-room comfort. A simple couch sits like found art center stage. It doesn’t budge, regardless of the setting. Scenes are all played out around the set, with the only alterations being a card table that is unfolded for a couple scenes, and upstage drapes that are opened for “outdoor” scenes played against the theater back wall. It gives a nice linkage to the old Chicago home in which this drama might have really taken place.

The deceptively familiar drama wears its sense of importance lightly, but seriously. Repeated references to James Baldwin’s second novel, 1956’s out-reaching ‘Gionvanni’s Room,’ promote that seminal book to audience members who may not be familiar with it, and there is much discussion of Bayard Rustin, the out Civil Rights leader who is credited with introducing M.L. King Jr. to Gandhi’s philosophy and organizing many of King’s biggest rallies, including the March on Washington.

Of course, in this crowd (on both sides of the apron) the decks of sympathy are stacked against Evy’s cause. Talk of “reorientation” sounds especially Medieval inside the Celebration. So it is that what lets ‘As Much as You Can’ get as good as it does is the honesty of the characters. What’s more, the scenes of openness, and the universe of intra-sexual and intra-familial, and intra-racial stratifications, surprisingly well represented in just a six-character play, could position the television version Stovall is working on for landmark status. It would be a smart move for HBO; a slam-dunk for Logo.

top of page

AS MUCH AS YOU CAN

by PAUL OAKLEY STOVALL

directed by KRISSY VANDERWARKER

CELEBRATION THEATRE

January 3-27, 2008

(Opened 1/4, rev’d 1/6m)

CAST Yassmin Alers, J. Nicole Brooks, Andrew Kelsey, Tonya Pinkins, Wes Ramsey, Paul Oakley Stovall, and J. Karen Thomas in for Pinkins 1/17 and 18

PRODUCTION Heather Graff and Rich Peterson, set/lights; Krissy Vanderwalker, costumes; Josh Horvath and Andre Pleuss, sound; Amy E. Stoddard, stage management

Andrew Kelsey, Paul Oakley Stovall, Tonya Pinkins and J. Nicole Brooks

David Elzer

More rush

It’s easy to get caught up in the youthful exuberance of ‘Bloody Bloody Andrew Jackson,’ a deconstructionist stage dive into the mosh pit of 19th Century history, aimed at rattling the pedestal of America’s 7th President. Written and directed by Alex Timbers, with music and lyrics by Michael Friedman, ‘BAJ’ mixes the raw energy of garage rock and the loopy madness of an improv troupe with a graduate student-obsession for righting U.S. history. However, its Kirk Douglas Theatre world premiere, through February 17 in a co-production with New York’s Public Theater, shows signs our graduate students were cramming as deadline neared. A long stretch of Act II has more information than inspiration, and (especially at an hour 50 without a break), it wears a little.

That isn’t enough to earn ‘BAJ’ many demerits, though. And, given the ingenuity of the creators, and the zest of the performers, it seems certain that New Yorkers will see a tighter show, with its storytelling and inventiveness more evenly spread across the whole piece.

The story roughly follows Jackson’s life, (Benjamin Walker) sketching in personal details from childhood, marriage and political ascent along with reasons for his early hatred of the British and the Indians to his military triumphs and the emergence of his political philosophy of populism. It’s a Technicolor tangle of style and substance, engaging music that crosses genres from Americana to contemporary rock, and uniformly strong performance spiced with tight comic timing and solid singing. This is held together by Robert Brill’s enchanting set, a fantasy environment of a 19th Century saloon dominated by a Natural History Museum Hall of Mammals diorama. The glass-enclosed taxidermy is a self-aware dare to anyone who thinks history theater need be of a museum piece.

The challenge, of course, is to be stylistically all over the map and end up with a clear perspective on Jackson. He is cavalier and conscientious, caring and dismissive, and all the time propelled by a disregard for the welfare of those in opposition – from the Natives to our British cousins. While it’s fair to present a man in all his complexities, the sincerity of the effort is compromised by the anarchy of the storytelling. Timbers and Friedman want to have it both ways and that they succeed as well as they do is testament to their considerable talents. It’s also likely they’ll do more than just smooth out the dry stretch in Act II, where Jackson’s troubles seeking consensus and popular engagement prove futile. That section can certainly be accomplished in less time. And, certainly the interaction of the rock star president and the citizens he meets across the country, is another opportunity for a musical number.

Still, the overriding tone is one of assurance. This group has grabbed their history by the neck, shaken the dust off it, and thrown its squirrelly ass against the barroom wall to see if it will stick. The facts are faithful, though the characterizations are a mix of everything from Grand Guignol to Vaudeville to Three Stooges. Of course, characterization is secondary to attitude, musical chops, and ability to switch from buffoonery to menace at the twist of a blade. And, speaking of blades, the 'blood' metaphor that flows through the narrative is dark and fluid, but may not clarify enough. Nevertheless, it's a bloody good day in the theater.

top of page

BLOODY BLOODY ANDREW JACKSON

by ALEX TIMBERS

music and lyrics by MICHAEL FRIEDMAN

choreography by KELLY DIVINE

directed by ALEX TIMBERS

KIRK DOUGLAS THEATRE

January 13-February 17, 2008

CAST Anjali Bhimani, Will Collyer, Diane Davis, Zack DeZon, Erin Felgar, Kristin Findley, Jimmy Fowlie, Patrick Gomez, Sebastian Gonzalez, Will Greenberg, Greg Hildreth, Brian Hostenske, Adam O’Byrne, Matthew Rocheleau, Ben Steinfeld, Ian Unterman, Benjamin Walker, Taylor Wilcox

PRODUCTION Robert Brill, set; Emily Rebholz, costumes; Jeff Croiter, lights; Bart Fasbender, sound; Gabriel Kahane, music direction/orchestrations; Jake Pinholster, projections; David S. Franklin, Elizabeth Atkinson, Michelle Blair, stage management

HISTORY World premiere.

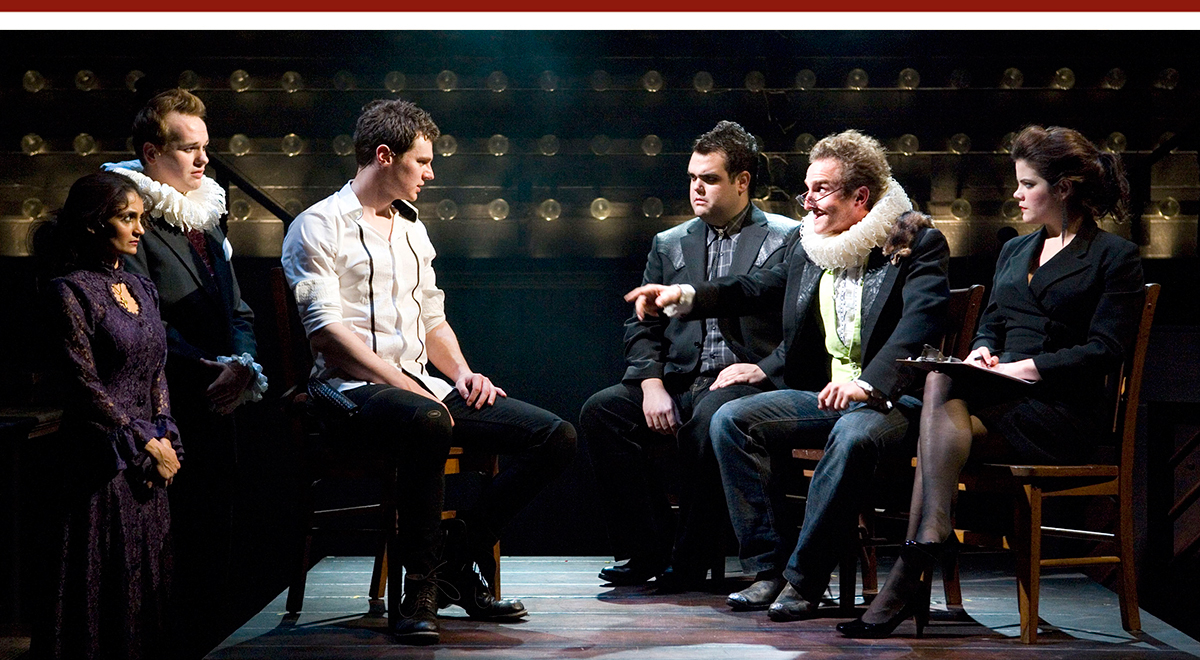

Anjali Bhimani, Brian Hostenske, Benjamin Walker, Greg Hildreth, Will Greenberg and Diane Davis

Craig Schwartz

Lapse dance

There is much to like about Josh Drake Johnson’s The End of the Tour, directed by Heather Dara Williams for Road Theatre Company through March 8. A sharp writer who can shape comic situations worthy of syndication, Johnson also has the playwright’s instinct for the drama beyond the jokes. In End, where the beast behind the blinds is both memory loss and memories that won’t leave us alone, he nearly creates an unforgettable play for the current caretaker generation dealing with Alzheimer’s and dementia.

Unfortunately, he’s unable to assign his three-prong story proper balance, and like the parent who lets his triplets clamor for attention, deprives us of properly getting to know any of them. Nevertheless, a visit to Road Theatre’s Lankershim space offers entertainment and insights, especially with Ms. Williams’ solid cast, led by Rhonda Aldrich as Jan with great work out on the fringes of this conflicted story from Michael Dempsey as Tommy.

Theodore Michael Dolas’ tidy three-section design, with hanging upstage panels ominously reminiscent of an old talk show set from the television genre that inform Johnson’s dialogue, serve as virtual isolation booths for the three pairs of characters. Stage right is Jan and Chuck’s (Tom Knickerbocker) kitchen. Center is the room in a nursing home where Jan’s mother Mae (Gwen Van Dam) is recovering from a broken ankle. And stage left is the nursing home’s waiting room where Mae’s son Andrew (Scot Burklin) and his lover David (Albie Selznick) spend the play in limbo while Andrew decides whether or not to go in for a visit.

Johnson sets his play in Dixon, Illinois, where Ronald Reagan was born and is now memorialized. For Johnson, it’s Reagan’s medical rather than political legacy that is of interest. Set in "the early 1990s," we assume the play precedes Reagan’s 1994 announcement that he had Alzheimer’s Disease. The story mechanics, which occasionally get parked for extended stretches while Johnson revs his comedy chops, center around Jan’s mid-life decision to stop nurturing and start living. She has long lived in Dixon, caring for her dull but loving husband and interesting but self-obsessed mother, a flamboyant former singer who once traveled with big bands and is angry that her touring days should end amid the nursing home’s mindless wanderers. Jan’s plan to end her tour of duty serving man and mother indicates she will now lean on her daughter for support by moving to the city where she lives.

Andrew’s arrival is not about mom’s troubles or Jan’s mid-life decision. He’s brought his own baggage, which seems to spring open upon arrival back in his birthplace. His story and Jan’s are so disconnected that after a first-scene phone call they never speak again. His role may be to show we (Jan) can’t run away from our past. Unfortunately, he ultimately does just that and gets away with it. Despite being a hallway away from distressed sister and distressing mom, Andrew never speaks to either again. Meanwhile, the writing is on the kitchen wall for Chuck, the extended family’s other spineless male member. While his old pal Tommy offers hilarious homespun counsel, he fixates on a non-responsive old cat who, like his marriage, apparently needs to be put to sleep.

The fraying of focus from these go-nowhere scenes would be more lamentable were it not for Dempsey, whose ear for Johnson’s comedy gives this third of the 90-minute one-act enough punch to withstand commercial breaks and still be worth the ticket price. His delivery of a line describing an alcoholic couple’s child-rearing style as "raising a family like two drunks on a pogo stick" is right on time. But it wants to be Jan’s play. And, appropriately, she is too passive to wrestle it back from her self-absorbed brother. One might argue that the title refers as much to Mae’s touring days as a singer (or even Andrew’s "tour" of the closet) as it does to Jan’s tour of duty as family ennabler. However, with all roads leading to Jan, and her eyes turned to the open road, giving her more of a chance to express herself would be helpful.

The missing scene, like in so many families, is the Jan-Andrew showdown in the waiting room. Unfortunately, those scenes seldom have resolution. But, ultimately, neither does this Tour. Near the end, when it becomes clear that the stories aren’t going to come together – Andrew won’t be confronting his mother, Jan may be off to inflict herself on her child, and Chuck may never get it – Williams indulges in a section of overlapping dialogue that symbolizes the cross-cancelling scene structure. If the indiscernible dialogue is dispensible, more’s the pity that when we want a real climax we get dismissible diddling.

But, that said, there is beauty in Johnson’s vision. There are occasional references to a lifeline, or memory thread, that is like the painted path hardware and other stores use to take customers from the information desk to the aisle they need. Losing our path and regaining it is the underlying metaphor, and it gets nicely book-ended by the late Johnny Cash, first appearing as defiant in Petty’s "Won’t Back Down" and then with his "I Walk the Line" closing the show. These, and Counting Crows’ "Sullivan Street" are fine choices by Johnson, Williams and/or designer Ken Sawyer, and give depth to the play fighting for its path within "The End of the Tour." For now that line is like the centerline on a foggy mountain road, and audiences may feel like another patient at Mae’s nursing home (Sylvia Little), trying to tell where she’s going or just what she’s seen.

top of page

THE END OF THE TOUR

by JOEL DRAKE JOHNSON

directed by HEATHER DARA WILLIAMS

THE ROAD THEATRE

January 18-March 8, 2008

(Opened, rev'd 1/18)

CAST Rhonda Aldrich, Scot Burklin, Albie Selznick, Michael Dempsey, Tom Knickerbocker, Gwen Van Dam, Sylvia Little

PRODUCTION Theodore Michael Dolas, set/lights; Jenny Green, costumes; Ken Sawyer, sound; John Boswell, music; Maurie Gonzalez, stage management (original production/development at Victory Gardens, Chicago)

Sylvia Little and Rhonda Aldrich

Matt Kaiser

Fight game

Stephen Drukman’s “In This Corner,” in a superb world premiere on The Old Globe’s ring-size Cassius Carter stage (through February 10), lets two legendary heavyweight boxers from the 1930s battle for personal dignity against the profit-and-propaganda process that turns people into products. In director Ethan McSweeny’s gritty staging, ‘Corner’ drapes its message loosely over these real-life champs, allowing us to learn about the men beneath the mantles as we gain empathy for 'products' then and now, in sports and beyond, whose extended “entourages” aren’t so much in their corners as in their pockets.

Central characters Joe Louis (Dion Graham) and Max Schmeling (Rufus Collins) reflect what, in hindsight, most ennobled their respective countries. African-American Louis validated our Algerian myth that all can succeed. Schmeling was a gentle man of humanity and an internationalist in an era of German empire-building and ethnic cleansing.

Several themes arc through the story like crosscutting trails off a shadow boxer’s gloves. There is the biographical material, told in an energized mix of flashback and forward motion. We learn much about them as individuals, their world championship fights in 1935 and ’38, and the mutual respect that served as friendship. A second theme, what Joni Mitchell called "the star-maker machinery," concerns the anonymous pack of jackals Drukman uses to set up the play: ‘the reporter’ (David Deblinger), ‘the photographer’ (Katie Barrett), ‘the trainer’ (Al White) and ‘the announcer’ (T. Ryder Scott), who rises to the role oracle at one point. They shape a play about machinating media and commercial interests into which the fighters will step.

That the champs wrestle the narrative away by play’s end suggests Drukman believes the individual is ultimately supreme. It certainly provides us a "feel good" play to take home, following a standing ovation at this performance and likely at most others.

A third theme emerges as the voice of this machinery. In the 1930s, radio added play-by-play sports coverage to its media arsenal. The world was still dominated by print media, but the electronic and broadcast segment had begun its move towards dominance. Families across the country now listened in unison to events like presidential addresses and heavyweight fights. And, in respect of that powerful presence, McSweeny stops the action to stage the 1938 fight merely through the power of words spoken first from the original broadcast, then picked up by Smith’s oracular ringside voice. The heightened language of the announcer, the sportscaster and the newspaper columnist give the show its bitter flavor, like a rum-soaked stogy. Drukman makes his point and dulls it with enough alliteration to give Howard Cosell salad-mouth. But it helps us see the parallels between the hypnotic power of speech in capitalist society and fascist society. The specter of Hitler (Scott) shows the "machine" at its most diabolical. While he and his ministers used athletes to promote their propaganda, America was using them to promote its counter-balancing righteousness.

In a country where African-Americans had 30 more years of legislated segregation before them, men like Louis (and later runner Jesse Owens), were asked to disprove the Reich’s fundamentalist Aryanism. In their first match, Schmelling prevails. In the second, Louis triumphs. Then, in one of their meetings before Louis' death at 56, Drukman creates a decisive "rubber" round, as the two meet in street clothes, and, quickly winded, wind up clasped in a wheezing tie.

As he did in 2006’s Body of Water, McSweeny has assembled a fine cast. Graham is winning as Louis, keeping him somewhat vague as he may have been to himself. (Though, more clarity from Drukman on exactly what happened to him in terms of drugs and mental illness would be appreciated as long as we’re presenting those aspects.) Smith is a stand-out, as is the great Al White, and Katie Barrett assumes the position from hard-boiled photographer to chanteuse to gum-soled nurse to high-heeled ringside attraction. And, a special commendation to Collins for a memorable Schmeling as well as (with assist credit to coach Jan Gist) a fine, understated German accent.

Ironically, the last time we felt a set integrated this well with its theater space was last year, next door in the Globe’s main stage with Ralph Funicello’s design for Restoration Comedy. Here, McSweeny and designers Lee Savage and Tracy Christensen go for the total realism of a boxing ring, turning the audience into spectators, with "off-stage" actors "ringside" as much as possible. The "you are there" sensation begins during pre-show with John Keabler’s sweaty workout as "the boxer." This detail accentuates the underlying metaphor of life in the ring, as when Louis bemoans: “We ain’t really nothing outside the ring Max,” or Max consoles his friend regarding public tastes: "Who are they? They aren’t even in the ring?" But the theme that Drukman floats like a butterfly is the flipside of language as instrument of propaganda.

Drukman works the seeking of autographs into the story as an indicator of fame. However, after all the alliteration has faded, and the hype has moved on to other more potent “products,” the fighters are left alone with a final friend and the simple words that are their names. Today, the traditions of Midway journalism are as strong as ever. After experiencing In This Corner, one may see our current celebrities

top of page

IN THIS CORNER

by STEPHEN DRUKMAN

directed by ETHAN McSWEENY

OLD GLOBE THEATRE

January 5-February 10, 2008

(Opened 1/10, rev'd 1/13m)

CAST Katie Barrett, Rufus Collins, David Deblinger, Dion Graham, John Keabler, T. Ryder Smith, Al White

PRODUCTION Lee Savage, set; Tracy Christensen, costumes; Tyler Micoleau, lights; Lindsay Jones, sound; Steve Rankin, fights; Jan Gist, voice/dialects; Diana Moser, stage management

HISTORY World premiere.

Dion Graham, Katie Barrett, Rufus Collins, Al White and T. Ryder Smith

Craig Schwartz

Cast a giant

There are numerous conflicts at play within Austin Pendleton’s Orson’s Shadow, the "inside baseball" theater piece in elegant revival under Dámaso Rodriguez’ direction on the Pasadena Playhouse main stage through February 17.

There are battles between out-sized egos, between sanity and madness, between theater and film culture, and even over acting choices. However, in this production, due in part to Bruce McGill’s oddly one-dimensional Orson Welles, these never provide any real tension or rise above detached discourse. What should be a spirited session with fascinating characters feels like a fly-on-the-wall look through the wrong end of the telescope: making the titanic tiny and tedious.

When famous people populate a play, we’re watching to learn about them, to learn about life through them, or both. There is a good deal to learn about these characters and, in theater-creature Pendleton’s take, the way they approached their primary professions: director Welles, actors Laurence Olivier (Charles Shaughnessy), Vivien Leigh (Sharon Lawrence) and Joan Plowright (Libby West), and theater writer/critic Kenneth Tynan (Scott Lowell). We get a mix of details about their pasts and present conditions during rehearsals for Olivier’s and Plowright’s appearance in Eugene Ionesco’s ‘Rhinoceros’ in 1960.

According to Anne Edwards’ biography on Ms. Leigh, who was separated from Olivier and involved with Jack Merivale at the time the play is set, the actress received a letter from her husband requesting a divorce around the time of the show’s opening. She responded by immediately releasing a letter to the press stating she would "naturally do whatever he wishes." In the process, she identified Olivier’s desire to marry Ms. Plowright as his motivation. That, according to Edwards, put Plowright in a tight spot as she was still married. Plowright bolted out of town to hide with her parents for a day.

We chronicle this not to contest anything Pendleton has included, or to challenge his focus on the relationships between the play’s three men. However, assuming Edwards’ account is true, the events not only seem more dramatic than what we’re watching, but more climactic. This play has one of the weakest endings in memory, with the narrative petering out before the show would open, and Plowright, in another strong effort from West, announcing that she is the only character still alive, she’ll fill us in on what happened to each. (In what might be a cute twist in a better-realized production, Welles and Olivier are just as curious as we are to hear what happened to them. Here, however, it just adds to the general lack of finality.)

Lawrence, an actress any production is lucky to have, has only minimal time onstage and her impact on the narrative is negligible. We are really in the hands of Tynan, Welles and Olivier. Tynan has managed to sell the nearly unemployable Welles to Olivier as director for Rhinoceros. Whether Welles will whip the show into shape before the others tire of him, whether the chain-smoking Tynan will keel over before some injured artist pummels him for a past notice, and whether Leigh will arrive stark raving mad to destroy the rehersal process are three primary areas for tension. (Welles’ assistant Sean, played by Nick Cernoch, is a handy foil for all plotlines.)

What happens during the two-and-a-quarter hour, two-act play, is that great histrionics are invoked for all these storylines, but it all gets bogged down in what feels like a technical rehearsal of a technical rehearsal.

The title suggests that all film-makers since Welles’ list-topping Citizen Kane work in the shadow of the Wunderkind. But there is also Tynan’s personal application. (And, within the tension triangle of Tynan, Welles and Olivier, the heart of the play is the fondness Tynan and Welles have for each other. This, too, is stunted by McGill’s portrait of a genius of bombast more than playfulness and subtlety.) Tynan offers an image of himself as a yapping dog, chasing beneath Orson as he floats across Europe like a bouncing hot air balloon.

Another area of interest is Pendleton’s placement of Tynan as a kind of fulcrum for the tottering giants Larry and Orson. Tynan represents a time when theater critics saw themselves more as part of the theater-creation establishment rather than drive-by snipers. At one point he chastises Olivier for being too defensive when he says, "Theater reviews need to be read with more intelligence."

If ‘TIME Magazine’ hailed this as one of the year’s 10 best in 2005, one suspects a substantially more engaging production got it there.

top of page

ORSON'S SHADOW

by AUSTIN PENDLETON

directed by DAMASO RODRIGUEZ

PASADENA PLAYHOUSE

March 8-April 8, 2007

(Opened 3/16)

CAST Nick Cernoch, Sharon Lawrence, Scott Lowell, Bruce McGill, Charles Shaughnessy, Libby West

PRODUCTION Gary Wissman, set; Mary Vogt, costumes; Dan Jenkins, lights; Cricket Myers, sound; Joel Goldes, dialect; Lea Chazin/Hethyr Verhoef, stage management (premiered by Steppenwolf Theatre Company)

Insets: Libby West and Charles Shaughnessy, top; Sharon Lawrence

Craig Schwartz

Executive style

Cheever and Updike have been acclaimed for prose focusing on upscale New Englanders, and Wilson has been canonized for building his century-long play cycle in an African-American neighborhood of Pittsburgh. A.R. Gurney, on the other hand, is more or less accused of chronicling WASP society. Fairly or not, he’s worn that label with increasing unease: the once-tailored sports coat that became a straitjacket.

Perhaps it was to distance himself from that reputation, and such boulevard annuities as The Dining Room, Love Letters, and Sylvia, that in 2006 he dawned the ill-fitting Post Mortem. An ambitious attempt at satire, Post Mortem, now receiving its West Coast premiere in an Insight America Touring Theater production stabled at the nearly finished Lyric Hyperion Theatre Café in Silver Lake, stabs wildly into the post-contemporary darkness.

His futuristic vision, much tamer but more specific than Orwell or Kafka, is of a post-Bush, post-Cheney, post-Gurney America in which his own post-script is a revival with the power to reverse the present president’s stifling legacy. The play is a switch on the plot structure that climaxes with someone pledging to turn the events we just watched into the play we just watched. In this case, however, with the play revealed at the beginning, it eventually becomes clear that the Post Mortem within Post Mortem is not the one we’re watching. That story had the power to alter history for the better. If only the one we’re watching had a fraction of that potential. Enough, say, to alter an evening for the better.

The American actors who can make farce enjoyable are few. How they do it would no doubt stymie a doctoral candidate. Here, the younger, non-Equity Andrea Syglowski exhibits a gift for it (even though required to go over the top in what is perhaps Gurney’s most egregious and irritating bit of non-relevance) while the elders seem to be in uneasy territory. Veterans Anna Nicholas (whose credits include respectable productions of Pinter and Ayckbourn) and Alan Bruce Becker, seem to be working too hard. Meanwhile Syglowski, who is directed to really push the envelop, manages to keep it fun and stay within the extremes, ending up with the most real character on stage.

Under Jered Barclay’s direction, an unreal world becomes an unnatural one. Paranoia and deviousness are telegraphed by facial muscle and eye-widening. Rather than helping tie together the play’s themes, which now seem to jostle about like broken blocks of floe, they seem to be poking them apart. Nevertheless, while more successful performances might have made the evening more palatable, it’s hard to see them making the play work.

Gurney sets the two scenes of this 90-minute one-act in 2017 and 2025. In the earlier era, the world has become oppressively conservative. Alice (Nicholas) is a flickering remnant of the great liberal arts tradition, a former actress now teaching theater at a faith-based university, which we infer has become the standard make-up of higher education in America. Naturally this means that faculty offices are bugged, dramatic performance is drawn from Biblical texts, and Broadway theaters are now casinos to cover debt from the Iraq War. (The incongruity of gambling dens as part of a religous order is just one of the lazy story creation.) Gurney has some fun elbowing sacred cows, with his favorite target being the glowering Mr. Cheney.

Dexter, a smitten student of Alice’s whose only real motivation is bedding her, is woefully ignorant of his chosen field. He doesn’t know who Tennessee Williams is, for instance, though in pursuit of the unimpressionable Alice he has gained an encyclopaedic knowledge of Gurney. Dexter has become the guardian of Gurney’s powerful final play, ‘Post Mortem.’ After seducing Alice with a dream scenario that includes first mounting the two-hander with him, then mounting him, the stage is set for Scene 2. Here, eight years later, the two Gurney-riders have, by somehow staging the play despite totalitarian repression, single-handedly changed the course of history, re-instating true freedom. They are now on a lecture tour at the same campus where they met.

The problem here is a script that might be called “impressionistic farce.” It’s not real farce – which is prickly enough to mount – but something even more vague. Nothing seems to add up. Unless the viewer is on political auto-pilot, and the mere utterance of Bush or Cheney can justify polishing up the wing-tips and leaving the embrace of the wingback for the night, this play is likely to have the entertainment value of an autopsy. At one point, Gurney parallels himself with the Almighty (paraphrasing: “He set it up but he didn’t tell us how to behave in it.”). As a creator, he has attempted farce without foundation. And, as any Master of Time and Space will tell you, one can’t create a universe without gravity and expect things to have weigh

top of page

POST MORTEM

by A.R. GURNEY

directed by JARED BARCLAY

INSIGHT AMERICA / LYRIC HYPERION THEATRE CAFE

January 9-February 17, 2008

(Opened 1/11, rev. 1/12)

CAST Anna Nicholas, Alan Bruce Becker, Andrea Syglowski

PRODUCTION Jeff G. Rack, set; Thomas Opitz, costumes/hair; Lara E. Nall/Joe Vain, stage management

HISTORY West Coast Premiere

Anna Nicholas, Andrea Syglowski, and Alan Bruce Becker

Loon landing

If the typewriting monkeys at TV Guide ever need to encapsulate a film version of Howard Korder’s ‘Sea of Tranquility,’ they may dub it ‘a therapist, heal thyself saga.’ However, such condensation isn’t in the forecast for Korder, whose plays burst with expansiveness, taking the long way home at a novelist’s pace so as not to miss the quirkier characters who have broken down along the way. As Michael Bloom’s staging at The Old Globe (through February 17) shows, Korder remains one of the most rewarding if underappreciated major writers in American theater.

Of his previous plays – ‘Boys’ Life,’ (1986), ‘Search and Destroy’ (1990), ‘The Lights’ (1993) and the epic ‘The Hollow Lands’ (2000) – his central characters were, in one way or another, out to lasso the moon. In both ‘Search’ and ‘Hollow Lands,’ there was enough blind ambition to propel those protagonists and their plot from one end of America to the other. In ‘Tranquility,’ which premiered at New York’s Atlantic Theater Company in 2004, the cross-country journeys have already been made. All but one in a parade of characters have arrived in Santa Fe from elsewhere in the hope of finding settlement.

Two main constructions preoccupy ‘Sea of Tranquility.’ There is the general issue of intrusion by foreigners on native land. This isn’t bumper-sticker clichés about mindless manifest destiny, but a broader swipe at those who lack a sense of the sacred, and invariably displace people who have it. Americans may not have invented expansionism or conquest, but we did give it a smug aura of self-righteousness, in denial that our actions have consequences. Korder’s plays balance on an internal beam across which a causal continuum slices: from awareness to responsibility and finally retribution or reward. How we pursue and accept the first two, respectively, determines which of the last two will befall us. (And from what height.)

To embody our national smugness, Korder has created Ben (Ted Koch), a transplanted New Englander whose surface calm is meant to project inner peace. But any appearance of tranquility within a Korder landscape is a mirage. Over the two-act, two-hour-plus play, Ben’s practice of doling out avuncular advice to his unsettled therapy patients will sound increasingly hollow, and his insistence that each person has the ability to change will backfire. Finally, his world of self-satisfaction will threaten collapse.

In Koch, Bloom has an actor who rightly maintains his calm, but cannot hint at the turmoil inside. The surface tension is there, but there needs to be glints of what’s underneath. It’s played as if being a sounding board for the other characters is sufficient to drive the story when it’s Ben who drives the story. Even when he doesn’t know where he’s going. This is a tricky assignment, given the overall sense that he has achieved his desired state of stasis. As his brother-in-law Randy, a man designed to be utterly without depth, Jeffrey Kuhn errs in the other direction. His performance is irritating enough to sandblast away any audience empathy the other characters have won.

Credit the Globe with casting a full stage of veterans and for the training program that has filled several meaty non-Equity roles with little drop off in quality. Among the vets, Erika Rolfsrud shines as Ben’s wife Nessa. She has the tough job of embodying the stuff of myth, and she does it with great (and appreciated) naturalness. Other stand outs are Nike Doukas, making one wish her small role had more stage time, the wonderful Ned Schmidtke (continuing his impressive string of performances from the Globe’s ‘Body of Water’ and Antaeus’ ‘Tonight at 8:30’), double-cast at unrecognizable extremes, and an appropriately grounded Carlos Acuña, also double cast.

Among the younger artists, Joy Farmer-Clary, in the pivotal role of Astarte, is excellent, and Sloan Grenz is good as a self-loathing genius teen. Tony van Halle, however, suffers the same blandness that permeates Koch’s performance. Whether one can justify these characterizations isn’t the point. They’re missed opportunities for something more interesting and engaging.

And, though it’s becoming repetitive to say so, this is another beautiful Old Globe production. Scott Bradley’s sprawling living room set creates a great playing area for the large cast, although it doesn’t seem in keeping with the economics of its owners, nor with the structure’s history of being built upon another home. Getting a sense of how Ben and Nessa really live comes instead from the writing, which includes a faulty spa that shorts out the home’s power. (A tip of the hat to the production department for an overflow scene that plays beautifully.) Credit Bradley with upstage wall textures that suggest cave-dwellers, and with that tie into the theme of the world that exists beneath – and before – our feet.

Korder has created a diverse world of characters and ideas in ‘Sea of Tranquility.’ The downside of such variety is the inability to spend more time with them. Still, one comes away with a sense of richness and plenty of questions over which to mull. And, as always, there are the little Korder gems tucked in along the way. Scenes or images that sear into the mind. Suddenly, in the middle of someone’s idle prattling, there will come the description of something so dark and haunting. One such incident in ‘Sea of Tranquility,’ like a moment iin ‘Sophie’s Choice,’ had that strange power in which a narrator innocently relates another person’s comments, unaware that they have just spoken what describes a deeper despair than most people ever grasp. When Astarte describes Donald, a lost soul seeking shelter in drug abuse, it recalls how Stingo quoted Nathan’s ‘We’re dying’ outbursts during lovemaking. Astarte tells how one night, an erect yet impotent Donald, stood naked in the foggy glow of an open refrigerator crammed with drugs repeating ‘I can’t believe I can’t believe.”

As an off-stage building contractor assesses about Ben and Nessa’s home, “When the footer is rotted, you need to dig down and see what’s underneath.” ‘Sea of Tranquility’ may appear a beautiful, almost glib sitcom of a play. But Korder has once more built his world on fetid footers. The studs and soleplates are the stuff of marital miscommunication; the limitations of pop psychology; our legacy of abusing land and each other. Audience members will be glad they spent the evening with this collection of reflective characters. Hopefully, they will be willing to dig down in search of awareness and responsibility. That’s where the real rewards are.

top of page

SEA OF TRANQUILITY

by HOWARD KORDER

directed by MICHAEL BLOOM

OLD GLOBE THEATRE

January 12-February 17, 2008

(Opened, rev'd 1/17)

CAST Ted Koch, Rosina Reynolds, Nike Doukas, Sloan Grenz, Erika Rolfsrud, Jeffrey Kuhn, Carlos Acuña, Joy Farmer-Clary, Ashley Clements, Tony von Halle, Ned Schmidtke

PRODUCTION Scott Bradley, set; David Kay Mickelsen, costumes; Robert Wierzel, lights; Paul Peterson, sound; Elizabeth Lohr/Moira Gleason, stage management

Ted Koch, Ned Schmidtke, Nike Doukas and Rosina Reynolds, top; inset Erika Rolfsrud and Koch

Craig Schwartz

Damned if you do . . .

The 2008 theater calendar got off to an encouraging start with the world premiere of Bob Clyman’s ‘Tranced,’ directed by Jessica Kubzansky, at the Laguna Playhouse through February 3. Strength of writing and strength of purpose combine to send a hopeful New Year’s message that playwrights still have the talent and tendencies to tackle tricky subjects. Clyman’s script pokes around several embattled institutions on the trail of a twisted cat-and-mouse tale. And it's all played out against the contemporary backdrop most likely to prompt our grandchildren to say, “Why didn’t you do something?”

In ‘Tranced’ – which specifically stands for Clyman’s contrived school of hypnotherapy, but more generally refers to the American public’s preference to sleepwalk over inconvenient truths – psychology, journalism and diplomacy each get their representative. Philip (Thomas Fiscella), Beth (Ashley West Leonard), and Logan (Andrew Borba), respectively, are attempting to help and/or use a young woman, Azmera (Erica Tazel), in whom the eyewitness account of a horrific act of genocide may be a repressed memory, as retrievable as audiotape in a desk drawer.

While Clyman questions the power and reliability of analysis, the motives and underlying principles of reporters, and whether diplomats and public servants deserve their reputations as mindless cogs, he makes duplicity the first-choice MO for all four characters. The playwright manages to make his case and “eat” it too: decrying the prevalence of deception in our culture, while cleverly employing it to serve up a mystery dinner complete with red herring.

A virtue of Clyman’s writing is the well-chosen detail. To paraphrase one character, “The bizarre detail is what leads people to assume something is true.” Clyman peppers conversations with Shitzus, little men with moustaches at parties, and Eskimo psychiatrists. It helps take us outside the cold abstraction of Narelle Sissons’ set – a game board floor of squares meeting an upstage window-pattern grid. The details also indicate Clyman has experienced – or meticulously researched – the worlds his characters inhabit, lending particular authenticity to Dr. Malaad’s “trancing” and Beth's newspaper demands.

By design, the play plays on perception, insisting that the true drama remain off stage. Bravely, Clyman and Kubzansky resist supplementing their staging with projections of gritty photography -- something subsequent productions will no doubt do. A single, recurring square of light comes and goes amid the upstage grid. Its significance is left to the reader to determine. However, when lighting designer Jeremy Pivnick streaks the upstage wall with a smear of blood-red sunset, there is no missing the significance.

There is plenty of meat here. The challenge for Clyman and Kubzansky is in tone. All the hiding of agendas beneath earnest ambitions limits each character to the same close-to-the-vest range within which to work. Compound that with a structure that requires talking about action rather than experiencing it in the moment and the static setting, and it becomes especially challenging for the viewer to follow subtle nuances.

Still, in Fiscella, the playwright has a terrific Malaad for his work’s premiere, and a central character who wins us over immediately and for the duration. Fiscella opens the show in direct address, directly addressing his international ancestry, which is Syrian, Egyptian and Jordanian. It sets us up for a story that may involve contemporary troubles in the Middle East, and occasionally misdirects our attention to anticipate that door may actually lead somewhere. There are several of these. But what the play, Fiscella, and the audience need is some more grounding, not additional loose ends. There are ultimately too many questions about too many characters, the confusing FBI report and Fiscella's history as a loner being two prime examples.

Tazel and Leonard have less success navigating their portrayals in the light of the writer’s undercutting storyline. They walk a thin line and it does add to the sense of sameness. One wants a little more variety from Beth. Reporters veer between a story leading to a Pulitzer or to just another day at the office. Where Beth falls is not quite clear. The task of injecting levity into the piece falls to Borba’s diplomat, and the actor makes the most of it, giving his character breadth while staying centered so his second act outburst remains within the range of realism.

Clyman has a delicate and worthwhile project here. It may need more of what film might bring the script. More tonal variety -- even if it's just visual -- might help focus. Fleshier characters would not only add interest, but further stack a deck he has already well-shuffled for this promising, entrancing game of four- card monte.

top of page

TRANCED

by BOB CLYMAN

directed by JESSICA KUBZANSKY

LAGUNA PLAYHOUSE

January 1-February 3, 2008

(Opened, rev’d 1/5)

CAST Andrew Borba, Thomas Fiscella, Erica Tazel, Ashley West Leonard

Borba, Leonard / Krieger

PRODUCTION Narelle Sissons, set; Julie Keen, costumes; Jeremy Pivnick, lights; David Edwards, sound; Rebecca Michelle Green/Victoria A. Gathe, stage management