AUGUST 2008

Click title to jump to review

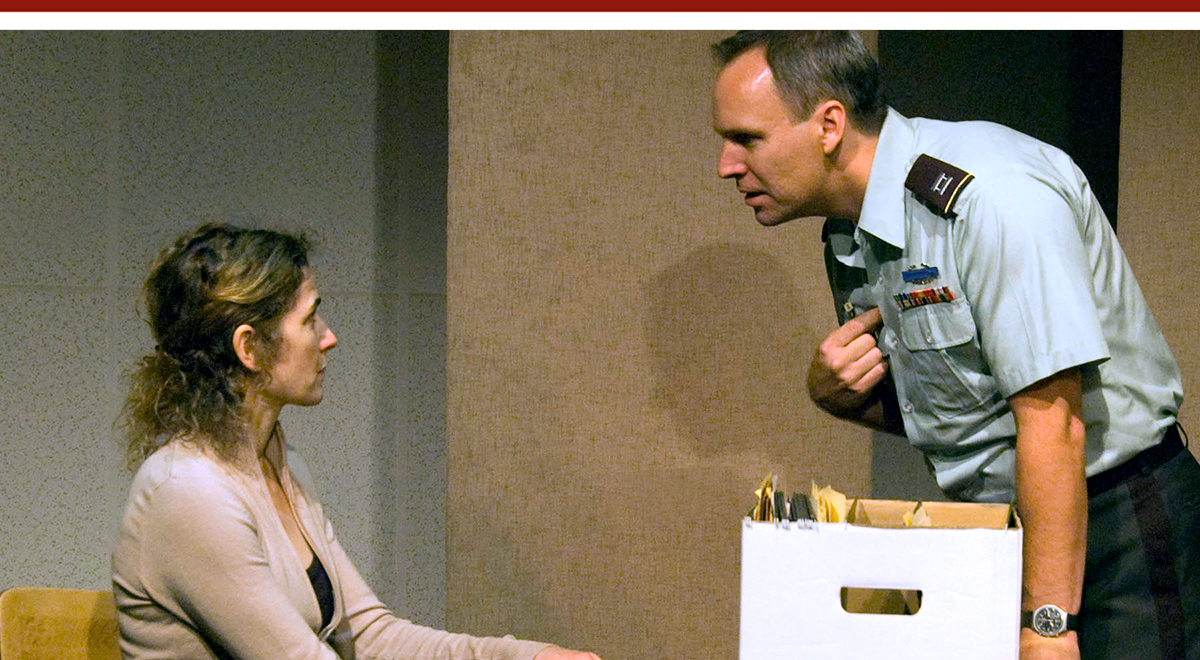

BODY POLITIC by Jessica Goldberg | Echo Theatre Company

FRANKIE AND JOHNNY IN THE CLARE DE LUNE by Terrence McNally | International City Theatre

GREAT EXPECTATIONS by Charles Dickens, adapted by Margaret Hooneman, Brian Van Der Wilt, Steve Lozier, Richard Winzeler and Steve Lane | Odyssey Theatre

SOME KIND OF LOVE STORY by Arthur Miller | Hayworth Theatre

VANITIES by Jack Heifner, with music and lyrics by David Kershenbaum | Pasadena Playhouse

Going Gray

War, the pop group, simply asked "Why can't we be friends?" War, the quagmire in Iraq, begs a tougher question: Have non-military American families become so indifferent to the war that veterans hospitals perform the medical equivalent of friendly fire? Are our returning wounded finding treatment programs a second battlefield, more surreal than those that put them there? In Body Politic, an ambitious attempt to claim the gray area between the extremes, playwright Jessica Goldberg wrestles with these issues through the relationship of political opposites who prove they can be friends.

The Echo Theater Company West Coast premiere, staged by Artistic Director Chris Fields, follows the play's March world premiere at Florida Stage under the name Ward 57. It continues at the Zephyr Theatre on Melrose through August 24.

While wholly welcome, it puts drama in jeopardy to portray the world through principled principal characters as circumspect as those in Body Politic. Popular political plays like Stuff Happens seethe with an author's righteous indications. Admirably, Goldberg brings even-handedness to the debate. She spares us the bold-stroke simplicity. And while she may sacrifice some dramatic clarity, itís in the service of human accuracy.

Body Politic is launched with the brief preamble of a wheelchair-bound Private Small (Jeremy Maxwell), pounding rhythm into his thigh as he works his horrific memories into rap lyrics. They are inspired. Small sustained wounds that blinded him to everything save the atrocities he participated in. In a snapshot, Goldberg has set down the elements of her story: the war, the wounded, and the way art appeals to those who need to explain them.

Captain Gray Whitrock (Michael James Reed) has returned from Iraq to take a job as public information officer at Walter Reed Army Medical Center. After getting nowhere by telephone, Wendy Hoffman (Kristina Lear) has shown up in person to ask permission to begin research on a docudrama about soldiers returning from Iraq. Whitrock, whose foot was amputated, has sustained enough damage to qualify him to talk as an equal with the wounded soldiers sequestered in the hospital's off-limits wards. He is the perfect shill for the job: a slight limp recalls his sacrifice, but it is little more than a scratch on the body politic. He becomes the presentable scab over a gaping wound the army does not want us to see, but that Goldberg wants us to imagine.

By getting to know Whitrock, Hoffman will move from serving the interests of her career and Hollywoodís coffers, to concern with individuals and truthfulness. As Whitrock moves to understand her, he will become less willing to hide the truth under the guise of protecting his country. In return, he gives his former adversary what we all need, an emotional stake in the war.

Fields has allowed his actors to find comfort with their characters, which is essential to the restrained honesty of this piece. Lear gives Hoffman a quiet loneliness, which in great part works to propel her through her scenes. Reed is genial, an affable stone-waller in no hurry to reveal how complicated his character actually is. Maxwell turns in one of the more impressive double-casting performances youíre likely to see. And Shelton successfully creates a woman wise beyond her experience.

Goldberg has several big issues in play here, and like a sandlot of seesaws they can all work independently and distract us from the one she most wants us to ride. While the sexual tension between Hoffman and Whitrock drives the story, it is buried at unacknowledged depths. It is the elephant in the room, capable on one hand of invalidating the non-romantic motivations of these two, or on the other of feeling under-explored. And a little bombshell dropped by Private Small, which would create something between front page headlines in The New York Times and war-crimes hearings at The Hague, must be assumed to proceed logically outside the story. It's place within the story is not properly addressed.

Even with these bumps, however, Body Politic is constantly engaging, subtle and smart. It is refreshing to watch an explosive subject handled this way. And if the real-people, shades-of-gray tone lets the storytelling fog slightly, we are better for the effort. Anyone who misses what the play is really about, will know when they leave. The spent soldier who opens the play searching for poetry in his lightless world, receives a ìdonít-forget-meî light cue at curtain. It may be docudrama, but in its heart, Body Politic wants to leave us with an emotional stake in our war.

top of page

BODY POLITIC

by JESSICA GOLDBERG

directed by CHRIS FIELDS

ECHO THEATRE COMPANY

November 6-December 14, 2008

(Opened 11/7, rev'd 11/8)

CAST Kristina Lear, Jeremy Maxwell, Michael James Reed, Samantha Shelton

PRODUCTION Torry Bend, set; Audrey Eisner, costumes; Ian Garrett, lights; Fionnegan Justus Murphy, sound; Lara E. Nall, stage management / produced by Lauren Bass and Chris Fields

HISTORY West Coast Premiere, World premiere at Florida Stage in March 2008 under the title Ward 57.

Kristina Lear and Michael James Reed

Jeffrey Howell

Dark Study

Dating a co-worker is a perilous proposition. While you share industry interests, workplace characters, and the opportunity to size each other up first, there's that chance you'll soon be spending eight hours a day avoiding someone who broke your heart – or, worse, had a broken by you. Still, as Barack and Michelle Obama happily related last week, office overtures can lead to historic partnerships.

The cook-and-waitress title characters in Terrence McNally's 1987 two-hander, Frankie and Johnny in the Clair de Lune (at the International City Theatre in Long Beach through September 21), have not been ear-marked for greatness, however. And, unless drastic measures are taken, they aren't even headed for happiness.

Painfully aware of this, chef Johnny (Thomas Fiscella) pestered server Frankie (Libby West) until she agreed to dinner and a movie. Late on that fateful date, somewhere between the moon and New York City, she invited him up to her apartment and with a window-full of moonlight, a classical station set to Johnny finds the &qyot;world's most beautiful music," and two midlife crises fast approaching desperation, Frankie's repressed desires get sprung with her convertible sofa.

That is where we come in.

McNally challenges his actors. Rather than introducing us to them at work and letting us get to know them as Johnny wears down Frankie's resistance (as the writer did in his revisionist 1991 film adaptation starring Al Pacino and Michelle Pfeiffer), we meet them in the dawning of post-coital lamplight. (Stephen Gifford designed the detailed, lived-in, but properly non-flashy environment.) Frankie insists he not spend the night; Johnny – spurred by a synchronistic series of coincidences – insists they spend their lives together. He spends the next two hours and two acts trying to change her mind. In the process, we will get to know them both.

Because Frankie does not want to reveal herself, West has the tougher job. She cannot even say why she is so resistant, lest she gives Johnny the keys to unlocking her resolve. The trick for the actors is keeping this from looking like handball practice as Johnny bounces his best shots off a wall.

What McNally has done to keep things moving is give Johnny an overcompensating gift of gab. As a result, he more than fills those empty stretches in which Frankie waits for him to say good night. Endearing eccentricities season his running monologue, like the love of spouting Shakespeare and juvenile catchphrases like "Pardon my French."

Director Todd Nielsen understandably wants these traits to be showy, but Fiscella doesnít quite integrate them naturally. He wears his eccentricities like a too-small cook's hat. The proof that it's not working properly comes when he shifts from the quirky salesman to sympathetic suitor. At the end of each act there are moments that play to Fiscella's strengths. And, he lands each one beautifully.

Similarly, in Act 1, West and Nielsen haven't found a way to open Frankie up to show a hint of what's behind her wall. We need to see both the flatness, which we get, and enough contour that indicates where the crack in her armor lies. This is probably the key to what hooked Johnny, and in the film the actors get much more chance to demonstrate without the pressure. Here it ís much harder.

The litmus test for a successful Frankie and Johnny comes when McNally idles his playwriting craft and hands the stage over to the music. The radio station playing during the show now plays an integral part of the story. Johnny has requested the dj replay something that caught his ear. When told that isn't possible, Johnny just asks for the most beautiful music ever written, in honor of this beautiful woman. If the show is working, we'll not only hear what Johnny hears in the piece, but see what he sees in Frankie.

By Act 2, after a round of mattress dancing during intermission, the crack has widened and West nicely loosens Frankie up. When her wall really comes down during the play's climax, these actors show what they are capable of, and we get McNally's pay off in a relationship that has a chance of making beautiful music.

top of page

FRANKIE AND JOHNNIE IN THE CLARE DE LUNE

by TERRENCE McNALLY

directed by TODD NIELSEN

INTERNATIONAL CITY THEATRE

August 26-September 21, 2008

(Opened 8/29, Rev'd 8/31)

CAST Thomas Fiscella, Libby West

PRODUCTION Stephen Gifford, set; Chris Kittrell, lights/sound; Michael Alan Ankney, stage management

Libby West and Thomas Fiscella

Bleak house

Perhaps the title page credit for "Production Attorney" should have raised suspicions. Having a defense team in place may indicate that a staging is prepared to be accused of offensive acts. Instead, Great Expectations, a new musical based on Charles Dickens' novel, was so well received during its April premiere at the Hudson Theatre that it has reopened as a guest production at The Odyssey Theatre (through September 7). Despite the critical clemency from the Los Angeles Times and others, we must indict on several counts.

Direction, acting, book, lyrics, music and physical production are the usual suspects for questioning in a theatrical shortfall. The fingerprints of all of them can be found on this body of work. Margaret Hooneman's adaptation wants to move the story's center of gravity towards Miss Haversham, the tragicomic character whose wedding-day jilting has made her both pathetic and predatory. But the book by Brian VanDerWilt and Steve Lozier doesn't offer the character more to chew on than the shell of Dickens' intentions.

The music by Richard Winzeler is probably the most solid element. At least it succeeds in not calling attention to its shortcomings. If it supported more interesting lyrics, it might even be engaging. But it is saddled with bearing Steven Lane's words, which neither dig around the story for fresh ideas nor sparkle with wordplay. They are literally devoid of poetry, which is not to say they don't rhyme. As one character sings, in a line that could have been about the lines she is singing, "I cannot erase them; I have to turn and face them."

The general problem is evident in "Ever the Best of Friends," a song early in the show that establishes the bond between Pip (Adam Simmons) and his brother-in-law, the noble put-upon Joe (Robert Arbogast). This is an opportunity to touch the complexities of Dickens' creation. There are rich ironies of a Victorian woman who has her blacksmith husband under her thumb, yet is known only as Mrs. Joe. Instead we have four or five minutes of generic buddy lyrics, with handshakes, promises of support, slaps on the back and big grins. Instead of digging into what makes Dickens Dickens, it feels as if we're trying to find what makes musicals universal.

It's also during this song that director Jules Aaron offers an indicative bit of staging flourish we would be better without. Five characters are sharing a section of song. But when three are temporarily outside the lyrical narrative, they freeze like Meissen porcelain until they can be incorporated again. It is understandable that Aaron is erring on the side of embellishment, given the lackluster lyrics. But, like Meissenware, it's best to shelve it.

No one should expect a production with limited resources to look like the RSC, but where money is tight imagination needs to pick up the slack. Certainly Dan Worenís Magwitch wouldn't arrive on the meshes with his striped prison shirt and slacks looking like they just came from the cleaners. The whole production has the feeling that the costumes (except for Haversham's wedding dress, which is a triumph for designer Shon LeBlanc) were grabbed by the actors before the shop distressed them. Adam Blumenthal's set, which offers a workable metaphor of the past and its memories incarcerated behind the gates of Haversham's Satis House, is dominated by a large flat of cheap white translucent fabric. One wonders if we would be better served just to have the gate.

Aaron's cast is largely the same as at the Hudson and it ís unlikely people saw a better show there. In fact, along with the continuing Zarah Mahler as adult Biddy, the most watchable actors are new - Annie Abrams as the adult Estella, Arbogast, and David Kirk Grant as Jaggers, the in-production attorney.

The two key figures are Pip and Haversham. Simmons has a strong voice, but not a lot of ideas on how to override the cyclical, serial nature of the travails Dickens has written for Pip. There isn't much build during the evening: He reacts one way to despair, and one way to opportunity throughout. Ellen Crawford's Haversham is clearly at the heart of this show's popularity as well as its sense of self. Crawford has a great look and can sing well. Unfortunately she's given little to do to artistically expose the deeper world that might exist within one of the quirkiest in Dickens' quirky pantheon. Two or three times she exposes the same wounds with little dressing up to move us further in the story or closer to her core. And, talk about running a good thing into the ground, Haversham is an onstage presence the entire show -- more than Pip.

Somewhere, one suspects Dickens and Haversham may be talking to their solicitors.

top of page

GREAT EXPECTATIONS

adapted by MARGARET HOONEMAN

book by BRIAN VAN DER WILT

and STEVE LOZIER

music by RICHARD WINZELER

lyrics by STEVE LANE

directed by JULES AARON

ODYSSEY THEATRE

July 17-September 7, 2008

(Opened 7/19, reviewed 8/8)

CAST Annie Abrams, Robert Arbogast, Dave Barrus, LJ Benet, Ellen Crawford, Britt Flatmo, Asunta Fleming, David Kirk Grant, Christie Herring, Kevin High, Troy Hussmann, Tricia Kelly, Matthew Koehler, Hap Lawrence, Zarah Mahler, Garrett Marshall, Steve Marvel, Brian Maslow, Steve Mazurek, Terren Mueller, Fred Pinto, Adam Simmons, Anthony Skillman, Kelsey Smith, Kailey Swanson, Karen Volpe, Dan Woren

MUSICIANS Berkeley Everett/Richard Winzeler, keyboards; Jamie Strowbridge, percussion

PRODUCTION Adam Blumenthal, set/lights; Shon LeBlanc, costumes, Calvin Remsberg, dramaturgy; Kay Cole, choreography; Brigid OíBrien, stage management

HISTORY An Odyssey Theatre guest production; return engagement after original production at Hudson Theatre

Adam Simmons

Miller's tale

By 1982 it had been 30 years since a handful of plays had placed Arthur Miller atop the list of American dramatists and 20 years since divorce from a handful named Marilyn Monroe had ended five years atop America's all-time female sex icon. On one hand Miller was looking to explore new forms of drama. On the other, he was haunted by the now-mythic form of an ex-wife who, 18 months after their marriage ended, had ended her life.

Those preoccupations form the ill-fitted hemispheres of Some Kind of Love Story, a one-act making its West Coast bow 26 years after Miller staged its premiere in New Haven. Michael Arabian directs the Hayworth Theatre production, which continues through August 31.

Miller has acknowledged his conscious motivation behind writing this play and its companion one-act, Elegy for a Lady. "[They] are of a different form than I've ever tried before," he told Matthew Charles Roudan in 1983. "Some Kind of Love Story concerns the question of how we believe truth, how one is forced by circumstance to believe what you are only sure is not too easily demonstrated as false."

Unfortunately, that explanation only confuses the issue. Not only is it clearly a verbatim transcript, which can make the best interviewee sound like Cheech or Chong, it sounds like a writer still fumbling after a phantom form. Not surprisingly, Arabian and his two-member cast - Beege Barkette as Angela and Jack Kehler as Tom _ all seem to have been dumped without a map into the show's apartment bedroom set (a surprisingly impersonal example of Prop Storage Chic by the usually resourceful John Iacovelli).

Miller's experimenting has done little more than pull the rug out from under his actors and audience.

It's the middle of a spring night in 1962, not coincidentally a few months before Monroe's suicide. A distraught Angela, unmade-bed sexy despite a new shiner from a man who has just left, is now awaiting the arrival of Tom, a 24-year NYPD veteran who became her lover while investigating a crime that she had witnessed. Tom still believes the case closed after an innocent man was convicted. He also thinks that Angela is hiding some fact that can free the wrongly imprisoned man. Unfortunately it, like her feelings for Tom and any hope for coherence in this story, are buried under her many layers of mental instability. Between her exorcising multiple personality demons and exercising her sex-for-money machinations, what she says is always suspect. (Even if Tom got something, it's unlikely her word would stand up in court, given her mental illness and history of bedding -- so she claims -- many key figures in the case.)

Still, hope of righting this injustice is Tom's stated reason for again leaving his wife's bed and risking a house call to Angela's. We begin to get the groundwork for a fascinating story about compulsive behavior, addiction to the wrong people, truth, lies and fantasy. Unfortunately, Kehler's cop is a theatrical flatfoot. If this play can work at all (and it apparently didnít in Millerís staging either), we need someone who can transmit this man's multi-leveled frustration, passion and anger. What Kehler offers is discomfort, weariness and some sense of moral indignation. He does offer anger. But the two or three times we see Tom's outrage, it explodes out of his placid demeanor like a monster bursting up out of a loch. It feels stagy and further hinders our engagement.

It must be reported here that press night was twice delayed a week, a not inconsequential bit of evidence in determining what has been committed here. That clue may or may not connect to Kehlerís half-dozen word stumbles _ roughly double this reviewer's (generous) allowance for a performance (even by a Non-Equity actor). For her part, Barkette also is asked to create a character with so much submerged and unexplained baggage that she is drowning in opportunities for overplaying. To her credit, she does not, except for scenes in which Miller and Arabian make her jump through multiple personality hoops. They don't really land, but she can be forgiven considering the general confusion of the enterprise.

Miller provided the opening tip to the personal dimension of this play by setting it just months before his ex-wife's death. Arabian closes the case with the second Angela costume he orders from designer Traci McWain. We won't spoil the moment by describing it. Let's just say it begs for a stiff breeze. But so does the cobwebby plotting of Miller's spider-and-fly tale. Whle an unusual amount of stage fog fills the house when audience members arrive inside the intimate Studio, it dissipates during the 75-minute show. Plenty of plot-fog, however, will be carried home by the audience.

A film noir version of the story was created by Miller in his screenplay Everybody Wins, starring Nick Nolte and Debra Winger. Those obsessed with solving the mystery of this odd one-act by the 1947 Pulitzer Prize-winner may want to investigate that work for clues to what happened here.

top of page

SOME KIND OF LOVE

by ARTHUR MILLER

directed by MICHAEL ARABIAN

HAYWORTH THEATRE

August 10-31, 2008

(Opened 8/16; rev'd 8/22)

CAST Beege Barkette, Jack Kehler

PRODUCTION John Iacovelli, set; Traci McWain, costumes; Frank McKown, lights; Bob Blackburn, sound; Joe Morrissey, stage management

HISTORY West Coast Premiere

Beege Barkette and Jack Kehler

Smash the mirror

The faces in the mirrors of Vanities, a new musical at the Pasadena Playhouse (through September 28) are as captivating to the audience watching them as to the characters wearing them. In fact, in Judith Ivey's staging of this update by Heifner of his 30-year-old play, Lauren Kennedy, Sarah Stiles and Anneliese van der Pol are so engaging that we might all be forgiven for joining them in ignoring what is being reflected around them.

Heifner has moved from playwright to librettist for this expansion of a play that, despite critical snubbing in its January 1976 premiere, became one of Off-Broadwayís longest-running shows. With the collaboration of composer/lyricist David Kirshenbaum ("Summer of í42í), it has grown by 12 songs and 16 years.

We meet the three best friends as high school cheerleaders in Fall 1963, the football season of their senior year, as college sorority sisters four years later, and during a rocky get together unofficially marking their 10-year high school reunion. A 1990 meeting has been added as epilogue for a clearer and happier ending than had been left with the playís original conclusion in the 1974 scene.

The musical premiered under Iveyís direction at TheatreWorks in Palo Alto and is scheduled to begin previews on Broadway in February 2009. As with the increasingly sturdy California crop of Broadway-bound musicals, this one is ready for its close-up. Anna Louizos' set is rich and inventive. Joseph G. Aulisiís costumes remain appropriate as they change through the periods and John Marquetteís hair and wig designs vary just enough to remind us that these are, at their roots, conservative women. (Although, let the record show that Joni Mitchell's "Clouds," depicted on Maryís wall, came out in 1969, the year after that setís last scene.)

The women are stars and the performances are chameleonic without being obvious. They age before our eyes thanks to subtle acting and costuming. They create recognizable people with a layering of social enigma. While all three characters are from Texas, only Stiles slathers on the Southern accent. At times it sounds like it could be used in canning fruit and you just wish sheíd can it. She can also, occasionally, go shrill in her singing. But these are minor complaints on three performances that elevate the show.

As eye-catching as the women are, however, they can't keep us from eventually sensing that there's an "elephant in the room" that is not being addressed. It's the question of how Heifner thinks these three women represent the impact, value, place or appeal of social and self consciousness in the '60s. Raising the question of consciousness-raising may seem heavy-handed in a play that appears to ask us to be no more critical of its subjects than we would leafing through a friend's photo album. But Heifner and Kirshenbaum have clearly stuck things in the background of their snapshots.

For one thing, the original play's time frame is in sync with the cultural '60s as opposed to the chronological '60s: from the assassination of President Kennedy to the resignation of President Nixon. More importantly, the first three songs depicting the girls' high school self-involvement do provoke our curiosity about how these three will navigate the coming liberation movements. But just when it looks like the play is going to avoid the larger issues and keep it personal to them, that elephant is brought to the center of the room with the song "I Don't Wanna Hear About It."

This is a direct rebuke of social matters, coming as it does following the cancellation of a Friday football game the night of the assassination in nearby Dallas. They then lump in their desire to resist the protest songs of contemporary "troubadours," which is a clear reference to Dylan et al. This clearly establishes the front end of an arc in which they will get more or less aware of the world around them. But it is a bridge to nowhere. As opposed to a character like Forrest Gump, who went through a similar time period, was in on everything and wanted to be impacted despite his disabilities, these three invest their intelligence in their own lives, which are too often defined in relation or reaction to someone else (usually men).

Ivey has given this Vanities an appreciable and appreciated sense of restraint, which includes appropriately minimal choreography that is always welcome and always close to character. The music is reminiscent of earlier styles - one might imagine Manilow singing a number, the Fifth Dimension another, and in the pivotal "I Don't Want to Hear About It," which briefly skirts with the big "consciousness" question, the band could easily veer out of its opening eight bars into Jackie Wilson's Higher and Higher.

In the end, Heifner's play is about friendship and not a statement about social responsibility and the value of involvement in things bigger than ourselves. It wants to be, but seems to have run out of will. Fairly soon, the elephant wanders out of the room. Perhaps, the women's lack of involvement in the world around them is Heifner's way of explaining a contemporary social mystery. It provides a profile of the people needed to elect one of the characters' fellow Texans to two four-year terms as President. Now it makes sense that the albatross elephant we've had in our living rooms for the past eight years got there because folks whose social awareness stopped with high school socials, mistook popularity for progress and made someone best suited for enlivening a Grand Old Frat Party into a world leader.

top of page

VANITIES,

A NEW MUSICAL

book by JACK HEIFNER

music and lyrics by DAVID KERSHENBAUM

musical staging by DAN KNECHTGES

directed by JUDITH IVEY

PASADENA PLAYHOUSE

August 22-September 28

(Opened 8/29, rev'd 8/30m)

CAST Lauren Kennedy, Sarah Stiles, Anneliese van der Pol

MUSICIANS Carmel Dean, conductor/keyboard 1; Marco Paguia, assoc. mus. director/keyboard 2; Michael Croiter, percussion; Joel Hamilton, bass; Gary Solt, guitars; Bob OíDonnell, trumpet; Phil Feather, reed 1; Jon Kip, reed 2

PRODUCTION Anna Louizos, set; Joseph G. Aulisi, costumes; Paul Miller, lights; Tony Meola, sound; Josh Marquette, hair/wigs; Lynne Shankel, orchestrations; Carmel Dean, musical direction/vocal arrangements; Pat Sosnow/Lea Chazin, stage management